By Rick Moore at American Songwriter

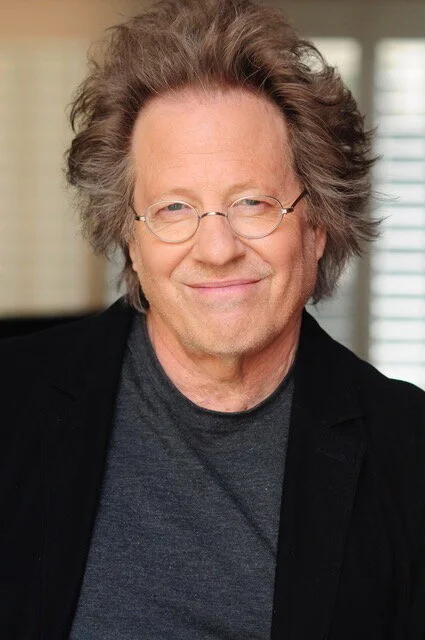

The list of Steve Dorff’s accomplishments in the music industry would fill a book. Actually, his book I Wrote That One, Too, which chronicles some of those accomplishments, is one of the things on the list. As a songwriter, arranger, pianist, producer, conductor, movie scorer and more, Dorff is one of the most accomplished and versatile musicians of his generation.

Dorff has written songs for George Strait (“I Cross My Heart”) and Celine Dion (“Miracle”), the themes for TV shows like Growing Pains and Murphy Brown, worked on the scores of five Clint Eastwood movies, and much, much more. His songs have charted in five successive decades, with No. 1 records across four of them. He called American Songwriter from his home near Nashville, where he’s been living for the past year or so after many years in LA, to discuss what he’s been up to lately, and to talk about synesthesia, a neurological condition that affects how people perceive music.

“It’s been crazy busy, I’ve been busier than I think I’ve ever been,” Dorff said. “I’ve been writing, producing four acts, getting ready to produce a new film project. I just did a duet with Barbra Streisand and Willie Nelson for her new album that’s coming out in the spring, I wrote that with Bobby Tomberlin and Jay Landers and I associate produced that as well. I’m working with a young band called the Nashvillains, kind of an outlaw band, and with a country artist named Liv Charette from Canada, she’s got a big voice. And I’m working on two tracks for Keb’ Mo’s new album, and writing with a lot of the great up-and-coming great writers here in Nashville.”

In 2018 Dorff was inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame in New York, joining the ranks of some of the greats who influenced him as a young songwriting hopeful. “You’re talking about Lennon and McCartney,” he said, “and the Gershwins, and Irving Berlin, and Paul Williams, and Mann and Weil—it’s the big one. I can’t tell you how honored I was to be inducted with my heroes. John Mellencamp and Kool and the Gang and Jermaine Dupri—it’s just a whole other strata.”

Where so many songwriters start out as musicians first, it’s always been all about the song for Dorff. “I was writing songs as a teenager and loving pop music,” he said. “I was watching these great artists, and saying, I want to write a song for that voice. I didn’t really sing well, and I didn’t have the dream of being James Taylor or Billy Joel, that wasn’t what I wanted to do, I didn’t want to be a performer per se. I just wanted to be writing songs for these great voices and be in the studio making records. That was always my ambition, to just write songs for people.

“Every writer develops their process,” he continued, “and it’s hard for me to steer too far away from my process, I still do it the same way. Sitting at my big Yamaha grand piano, that to me is still … the sound of those keys is what’s inspiring to me. I won’t co-write with more than two other people, it’s generally just me and one other person.

“I’ve done tons of everything,” he said. “I started as a session player in Los Angeles, and got into arranging sessions for so many artists, and that kind of led to the production desk. I love working with big orchestras as well, and during this pandemic I’ve done something that I’ve wanted to do my entire life but really never had the time to do, which is write a piano/orchestra concerto, and hopefully will be having a premiere maybe later this year. In my career, I think the thing I’m most proud of is the diversity, the fact that I’ve had so much success in pop and country and R&B and film and television, it’s kind of kept me on that wheel. I’ve just been very blessed to have been able to dip into those different genres and have success in each of them.”

One might almost assume that someone with Dorff’s background as a pianist and orchestrator must be classically trained, maybe studied at a place like Juilliard or Berklee. But Dorff is completely self-taught, and part of his musical gift comes from his having synesthesia, the sensory phenomenon that leads people to perceive music as colors and in other ways.

“I have this thing from probably in the crib,” he said. “I didn’t know what it was of course and I assumed everybody had it. It’s called synesthesia. I saw colors and bubbles like a lava lamp as a kid when I closed my eyes and heard music. Before I knew what a bassoon or a clarinet or an oboe were, I was hearing these orchestrations in my head. I was a weird kid, I had this gift of a mini-orchestra in my head. My biggest challenge as I grew up was how to get this out of my head and onto paper. So I’d go the library and study the great orchestrators, the arrangements, and taught myself how to read. And that’s pretty much how I’ve done it.”